Listen to Arthur’s fascinating story and memoirs:

Click here to read Arthur’s memories

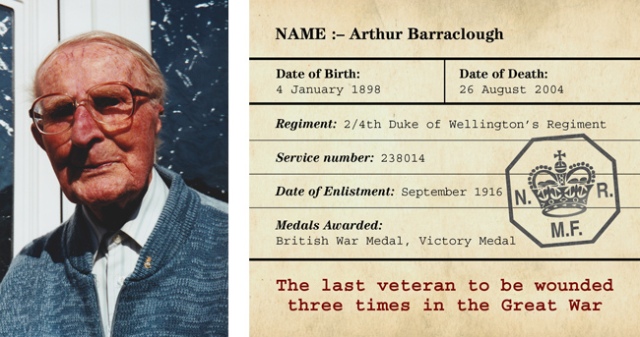

Private Arthur Barraclough, 2/4th Duke of Wellington’s Regiment

The Last Veteran to be wounded three times in the Great War

Born in Bradford in 1898, Arthur began work as a hairdresser in the town before receiving notice of his conscription into the army in January 1916 although he was not called up until September. After training, he was posted to France the following January, joining his battalion, 2/4th Duke of Wellington’s Regiment in the field.

Arthur was wounded in the arm in March 1917 but was sent back to his battalion to take part in the Battle of Arras, and went over the top. He was wounded again, more seriously, in November that year and returned to England and hospital where he remained until mid March 1918.

He went back to France in April to serve with the Regiment until the end of the war. He remained overseas for several weeks after the Armistice working with German prisoners to clear the battlefields of unexploded ammunition, a dangerous job that cost the lives of two comrades in one tragic incident that affected Arthur badly.

It was early 1919 when he returned to Britain and resumed his career in hairdressing. He married and had one son, and eventually retired to Morecambe. Aged over 100, he was interviewed about his experiences by the BBC, appearing in the final tribute to the Great War Generation, ‘The Last Tommy’. He died in 2004 aged 106.

Follow Arthur’s memoirs below in his own words:

Some lads used to get drunk when they knew they were going over the top, and they’d go over fresh, others used to grab onto someone else, they’d be frightened to death, but I wanted to act like a man.

I could face up to what was coming. So I used to say a prayer before I went over. ‘Dear God, I’m going into great danger, would you please guard me and help me to act like a man. Please bring me back safe,’ and I used to go out without a fear. I went over with confidence.

We had been practicing for weeks going behind these tanks, a platoon behind each, in two ranks. Now we could hear them coming a mile away, and four tanks got set up in front of our trenches. We set off behind one of them.

The idea was that when it came across the German line, it was supposed to flatten the wire and our platoons would open out and attack. The problem was there had been a lot of rain at the time; it was terribly flooded. We had hardly gone twenty yards when the tanks got stuck in the mud, and others went nose down into old trenches.

The tanks had bundles of wood tied to their tops and these were supposed to be dropped into the hole to give the tank tracks some grip to get out, but it didn’t work that way; the tanks were too heavy and smashed the wood. None got any further than the first line of trenches and not one of them reached the objective on our bit of front.

Meeting the enemy

I came across a badly wounded Jerry and he was shouting out:

Water, water!’ I just stopped for a second, and thought ‘I’ll give the so-and-so a drink,’ and a sergeant shouted, ‘Barraclough! Get on with your work, don’t worry about him.’

I suppose he thought he might have had a gun or a bomb in his hand, perhaps the sergeant thought I was trying to dodge the attack, I don’t know.

I felt really hurt, though, to leave that fellow there with half his face blown off and me walking past. I’ve thought many times, if he’d lived, what he’d have thought of a British soldier who knew he was wounded and wouldn’t give him a drink. I’ve never forgotten that man. He haunted me a bit.

The death of mates

The battalion was being held up in an attack, and we were told to take the Lewis Gun and go to the flank and enfilade the enemy. So we found this old building, it was only a few bricks, and we got down and gave them a blast or two.

I was lying beside the gun, firing it, and the other two lads were behind, filling the magazines. Within a minute, bullets started flying past us and then shells started to come over and one hit bang in the middle of the four, but all the blast seemed to go one way, taking the gun and the two lads with it. They completely disappeared but the gunner and I were untouched.

Within a couple of days of losing my mates I was wounded in the heel while out collecting rations. I was picked up and sent down to a base hospital where, through a bit of luck, I was sent to England and a hospital in Wigan. While I was there a couple of people came round the wards with a list of missing soldiers.

They asked if we knew anyone called so and so, and they called out one of these lads’ names who’d been with me in the machine gun team, so I said:

‘Yes, I know that lad, he’s dead.’ They asked, ‘Are you sure?’ and I said, ‘As sure as I can be, he just got blown to bits.’ Then they asked me, ‘Would you like to go to Chesterfield? That lad you just named lived there and it would be a great pleasure to us if you could go and tell his mother, tell it to her nice, that he isn’t a prisoner of war or anything like that, that he won’t be coming home.’

The man had lived in a mining district. I found the house and told them they wouldn’t have to expect him coming home. I said he was killed, but didn’t tell them how it happened. They had been hoping he was a prisoner, and I had to say to them:

‘Sorry, no, I know for a fact he won’t be coming home’. It was a bit of a hard do for them. He was only a young man like myself, about twenty. They were heartbroken but they thanked me for going to tell them.

Very interesting read about one of the soldiers lives fighting on the frontline of world war one.fighting for their lives and country.they cannot have had a good time in the trenches.but some have lived to tell the stories and tragedies of world war one.

Honours for a Barraclough Ancestry I inherited.